I am continually fascinated by the intersection of contemplative religious traditions and science, specifically theoretical physics. Time and again, they employ very similar language to describe almost identical concepts, however differently those concepts were developed. I use my art-making techniques as a physical meditative process in which I attempt a deeper understanding of these subjects, the focused attention I give my fragile and ephemeral materials giving them a temporarily elevated value and identity.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Statement for Creation Stories

Both quantum mechanics and Buddhism postulate that no thing has an intrinsic identity. Every thing – and person – is created and defined by its relationship with other things. We are, in fact, dynamic processes that hold a distinct form for only a brief time. We are, and only are, the result of our interactions and relationships. Aspects of reality and consciousness in Buddhism and the spacetime of quantum gravity have both been described as active, intricately connected nets.

Quantum physics and Buddhism also acknowledge that at the most fundamental level, no absolute division can be made between mind and matter. Buddhism goes further to say that world systems (multiple and/or successive universes) come into existence in response to the karmic need of sentient beings.

The mandala is a representation of the cosmic universe, in a circular pattern that leads to a central point. It also represents the human journey from ignorance to Buddhahood. It is a symbol of active wholeness, of beginning and end.

Buddhist texts refer to the cosmos as “the container” and sentient beings as “the contained.” In art and many cultures, vessels are also used to symbolize reproductive life and creation.

I’ve recently decided to count my gardening practice as part of my art-making practice and to allow them influence one another.

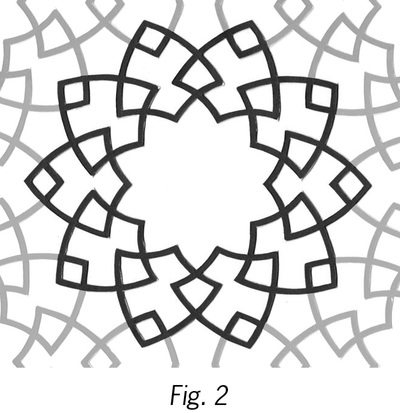

A special note about Creation Story: Knots - These pieces were inspired by a series of wood engravings by Albrecht Dürer called Six Knots, which were in turn heavily influenced by similar designs by Leonardo da Vinci, which had roots in Coptic manuscripts with Arabic influences. Da Vinci’s linked, symmetrical knots are formed by a single cord that can be traced in a continuous complex loop, the whole of which fills a round space. There are theories that they were intended as meditative labyrinths and/or coded symbols for diagrams of the cosmos.

Both quantum mechanics and Buddhism postulate that no thing has an intrinsic identity. Every thing – and person – is created and defined by its relationship with other things. We are, in fact, dynamic processes that hold a distinct form for only a brief time. We are, and only are, the result of our interactions and relationships. Aspects of reality and consciousness in Buddhism and the spacetime of quantum gravity have both been described as active, intricately connected nets.

Quantum physics and Buddhism also acknowledge that at the most fundamental level, no absolute division can be made between mind and matter. Buddhism goes further to say that world systems (multiple and/or successive universes) come into existence in response to the karmic need of sentient beings.

The mandala is a representation of the cosmic universe, in a circular pattern that leads to a central point. It also represents the human journey from ignorance to Buddhahood. It is a symbol of active wholeness, of beginning and end.

Buddhist texts refer to the cosmos as “the container” and sentient beings as “the contained.” In art and many cultures, vessels are also used to symbolize reproductive life and creation.

I’ve recently decided to count my gardening practice as part of my art-making practice and to allow them influence one another.

A special note about Creation Story: Knots - These pieces were inspired by a series of wood engravings by Albrecht Dürer called Six Knots, which were in turn heavily influenced by similar designs by Leonardo da Vinci, which had roots in Coptic manuscripts with Arabic influences. Da Vinci’s linked, symmetrical knots are formed by a single cord that can be traced in a continuous complex loop, the whole of which fills a round space. There are theories that they were intended as meditative labyrinths and/or coded symbols for diagrams of the cosmos.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Statement for Elementals

Renaissance science, with its Aristotelian basis, was replete with mysterious connectivities and influences. Objects were invisibly bound to each other by inexplicable yearnings and affected each other in curious ways. Alchemy, the medieval forerunner of chemistry, through a variety of enigmatic physical and mystical methods, worked to purify, perfect and transmute material objects, the human body and the soul, with the goal of achieving wealth, good health, immortality and transcendence. Alchemists believed that the purity of their bodies and minds influenced the chemical reactions they created – that their conscious intentions affected the material world.

The subsequent encroachment of the Newtonian worldview caused these beliefs of connectivity to give way to the understanding of separability and the theory of determinism, which explained the world from a much more mechanistic viewpoint, abandoning the notion of objects and interactions being influenced by human consciousness. This was the basic understanding of the world for a couple of centuries.

Today, quantum physics has revived the concept of interconnectedness on a fundamental level. Energy and matter, space and time, are intricately entwined with each other – two sides of the same coin. In addition, though it’s controversial within the physics community, the theory of quantum entanglement addresses the observation of influence by human consciousness on particles within quantum experiments. The ancient alchemists could never have proved interconnection on this level, but this unexpected discovery by modern-day scientists gives me a satisfying sense of coming full circle.

In this body of work, Elementals, I imagine the power of our personal intentions and consciousness to influence, and even create, the world around us.

The title Elementals comes from the German Renaissance alchemist, Paracelsus, who envisioned elementals as symbolic beings that were something between spirit and human. Each elemental personified a natural element – earth, water, air or fire – and therefore possessed the powers to generate, manipulate and transmute their particular element. Humans were considered to be a combination of all the elements and to have influence over them all.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Statement for Theories of Everything

John Muir wrote, “When we try to pick out anything by itself we find that it is bound fast by a thousand invisible cords that cannot be broken, to everything in the universe.”

This body of work takes inspiration from the “thousand invisible cords” of modern string theory, ancient Islamic sacred geometry, and the principles of ecology. These complex areas of study have several overlapping concerns: the harmony of relationships; the correlation between the very large and infinitely small; symmetry; repetition; beauty; an appreciation for the elegance of a perfectly balanced system; and the extreme interconnection of everything.

We as a species are doing our best to deny that our survival is enmeshed with all other life on the planet. Subsequently, although the facts of climate change are becoming impossible to ignore, the damage we are doing to our delicately balanced ecosystem will also be denied - possibly to the point of no return. This distressing prospect prompted me to delve into ideologies of an ageless and unabating universe, in hopes that in comparison to a much more vast reality, our failures would not seem so momentous.

In much of my past work I have explored the thought systems human beings use to understand the world and themselves. Science, geometry, mathematics, religion, poetry, mythology, music; all are the result of our attempts to puzzle out the mystery of existence, and they all describe a different part of the same story – and, though the methods differ, they often reach strikingly similar conclusions.

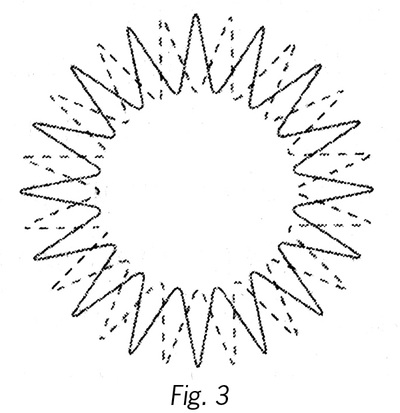

String theory within the study of physics came about in an effort to unify two other theories: special relativity, which deals with objects and spaces on a cosmic scale; and quantum theory, which pertains to the microscopic world. The result is the poetic idea that all matter is the result of the resonances of vibrating microscopic loops (dubbed strings). Each resonance travels through several hidden spatial dimensions to produce the physical signature of an elemental particle, and those particles work together to create everything in the universe.

The sacred geometric art of Islam is in many ways an ancient, symbolic version of string theory. To quote Keith Critchlow in his book Islamic Patterns - An Analytical and Cosmological Approach, “The overriding principle…is the unity of existence and therefore the universe. This unity has always an inner and an outer aspect – a hidden as well as an outer way of studying cosmology. The outer embraces sensible observation, the inner is appreciating the expression of cosmological laws within one’s own structure. The goal of spiritual disciplines is to unite the inner and outer, the greater and smaller, into an inseparable integrity.”

I was struck, not only with the similar goals of these two thought processes, but with the similarity of methods, language and visuals. Although the Islamic patterns have a spiritual dimension to their explanation of the universe, and string theory is only concerned with the physical aspects of matter, they both endeavor to trace the pathways of creative energy.

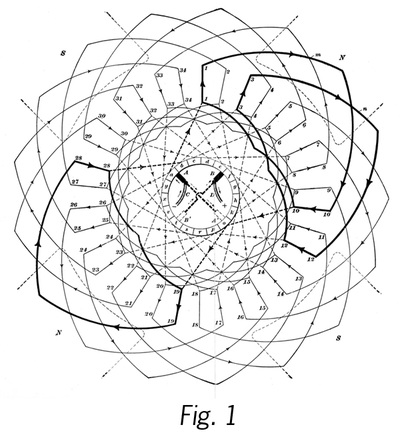

Much like the diagram of a motor’s electrical generator traces the path of electricity as it courses along its copper coil (Fig. 1), the Islamic patterns (Fig. 2) are diagrams of energy trajectories in their route from the Origin to spiritual and physical manifestations, and back again. Similarly, the strings in string theory generate the creative energy of all matter through their vibrational journeys (Fig. 3).

As I create these pieces, I am comforted by the harmonious patterns. I can attempt to align myself with pathways of endless creativity and regeneration; an energy that will not be defeated by greed and apathy. These theories offer the reassurance of an all-encompassing structure within the universe that will persevere. The temporary event of our existence is put into perspective by the contemplation of the sacred and perpetual nature of reality.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Statement for Selfless

An on-going series, Selfless explores several ideas. The main concept behind these pieces is the Buddhist idea of removing one’s self, or ego, so that the creative force of the enlightened mind can operate freely within one’s consciousness. The missing figures create an eerie sense of loss, but the world has filled in behind the silhouettes, giving them another sort of shape and form – a memory of sorts, but also an indication of the continuity of the world despite the loss of an individual. The use and destruction of old photographs not only questions the value of the photos themselves as objects, but also the durability of treasured memories, and the sense of self we derive from those memories.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Statement for Structure of Accumulation

The Structure of Accumulation series was influenced by several sources, from religious art of the past, to recent scientific discoveries. The first is the ancient form of Buddhist mandalas, which use simplified floor plans as metaphors for the structure of the human soul. The Structure series proposes that the modern soul would reside in a somewhat less well-proportioned structure than those represented by the mandalas. Supposing our psychological/spiritual selves are formed by what we think – in the way our bodies are composed of what we eat – modern-day souls are made not only of responsibilities shouldered, love shared, curiosities and daydreams, but also of the immense amount of information we absorb, the stress we cope with, the frustration we repress, and our pervasive multi-tasking habits. Existing in a spiritual space of manipulated perspective similar to that of Medieval religious paintings, the buildings in the Structure series show that the architectural versions of our modern selves feature some strong basic forms, but there are also dark, disturbing rooms in the basement, stairs that lead nowhere, rickety support structures that could fall at any moment, and odd rooms added to the original building in order to accommodate new ventures. The ‘building materials’ are gathered from the never-ending stream of input we encounter daily, both good and bad.